During this recent visit to Washington DC, I was able to photograph the newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). As the 19th and newest member of the Smithsonian Institution and its fabulous family of museums, this new museum is also jokingly referred to as the "Blacksonian". New York Times art critic Holland Cotter, picked the museum as his #1 choice for the Best Art of 2016

View of the Museum and the Washington Monument with the traffic on 14th Street at dawn

Thirteen years in the making, after being established by an Act of Congress in 2003, (or a century if you consider the 1916 congressional bill proposing “a monument or memorial to the memory of the negro soldiers and sailors”) the Museum opened to the public on Sept 24th 2016. It serves as an amazing reminder of the influence that African American culture has had not just on the US but also on how the rest of the world sings, dances, speaks, dresses, eats, plays and works. Built on the National Mall in Washington DC, it's right next to the Washington Monument and a short distance from the White House.

A street level view of the Museum from the intersection of 14th Street and Madison Drive

The design and construction of the Museum was one of the largest and most complex architectural projects completed in 2016 in large part because of the challenges of constructing 60% of the structure below ground within the DC tidal basin.

The Museum and clouds reflected on the black granite retaining wall along Constitution Avenue

The resulting design team of four architectural firms, Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup (FAB/S), was one of six finalists selected to present design proposals to the Smithsonian, ultimately winning the design competition in April of 2009, beating out other big name architects such as Moshe Safdie, I.M. Pei, and Norman Foster for the coveted $540 million government commission partly funded by countless small, and large private donations

View of the Museum from the main entrance with the shadow of the Washington Monument

The Museum and the Washington Monument reflected on the black granite retaining wall

View of the Museum as the sun sets over the National Mall

The Museum which houses 36,000 artifacts throughout its 400,000 square foot space is more than just a museum - it is also a monument to African American history, community and culture.

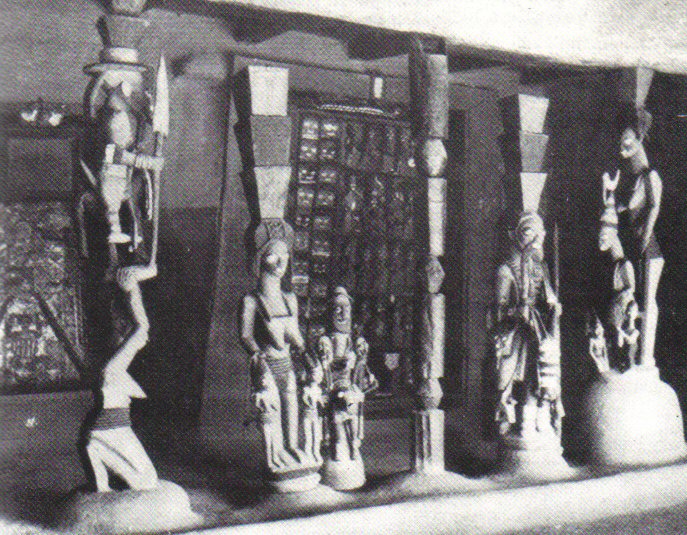

According to the lead designer, the British Ghanaian architect David Adjaye, his team got the job by keeping those three aspects of the project in mind—history, community, and culture. It's an integral design aspect of the building's distinctive tripartite corona form which draws inspiration from the Yoruban Caryatid, a traditional wooden column which features a crown or corona at its top. The concept came from research into the beginnings of slavery in Central and West Africa and study of Yoruban culture. The below image of carved wood sculpture by the Nigerian artist Olowe of Ise shows the tripartite crown on the two figures on either side of the central column.

Yoruban caryatids and carved door - Image courtesy Rand African Art (www.randafricanart.com)

Details of the bronze colored corona panels that give the Museum its distinctive shape

The bronze-colored corona panels draw inspiration from the ornate ironwork found in Charleston, Savannah and New Orleans. The design team studied this historic iron lattice work, in many cases created by enslaved Africans, and created the light-permeable façade of the museum by digitizing the traditional shapes and transposing them into a modern interpretation, scaled to the size and shape of the building.

Details of the bronze colored corona panels on the front facade of the Museum

The distinctive Yoruban crown shape of the Museum and the bronze colored corona panels

The exterior design is successfully able to draw upon and beautifully meld familiar imagery from both African and American history.

In one of his interviews discussing the Museum, Mr. Adjaye says that the best way to experience the museum is by starting at the basement level. There, from the galleries portraying the origins of slavery, one climbs up to the upper levels to ultimately view a display about president Obama. He refers to this progression from the museum’s dark subterranean chambers to the bright and joyful galleries on the top floors evoking the African American “journey into the light”. “That’s the emotional power of architecture, to bring you into a journey and to give you uplift,” Adjaye said. “The greatest cathedrals, temples and shrines give you uplift, and I think architecture is best when it supports the narrative through the articulation of space.”

Visitors taking in the view of the Washington Monument from the Museum at dusk

View of the Washington Monument and the Museum with the evening traffic on 14th Street